Most AI tools do one thing well: answer questions, summarize text, or generate content. NobelLM does something different—it adapts its response style based on what you’re actually looking for.

I built NobelLM to handle four distinct types of queries. (Read about why I built it here.) Here’s how that plays out in practice.

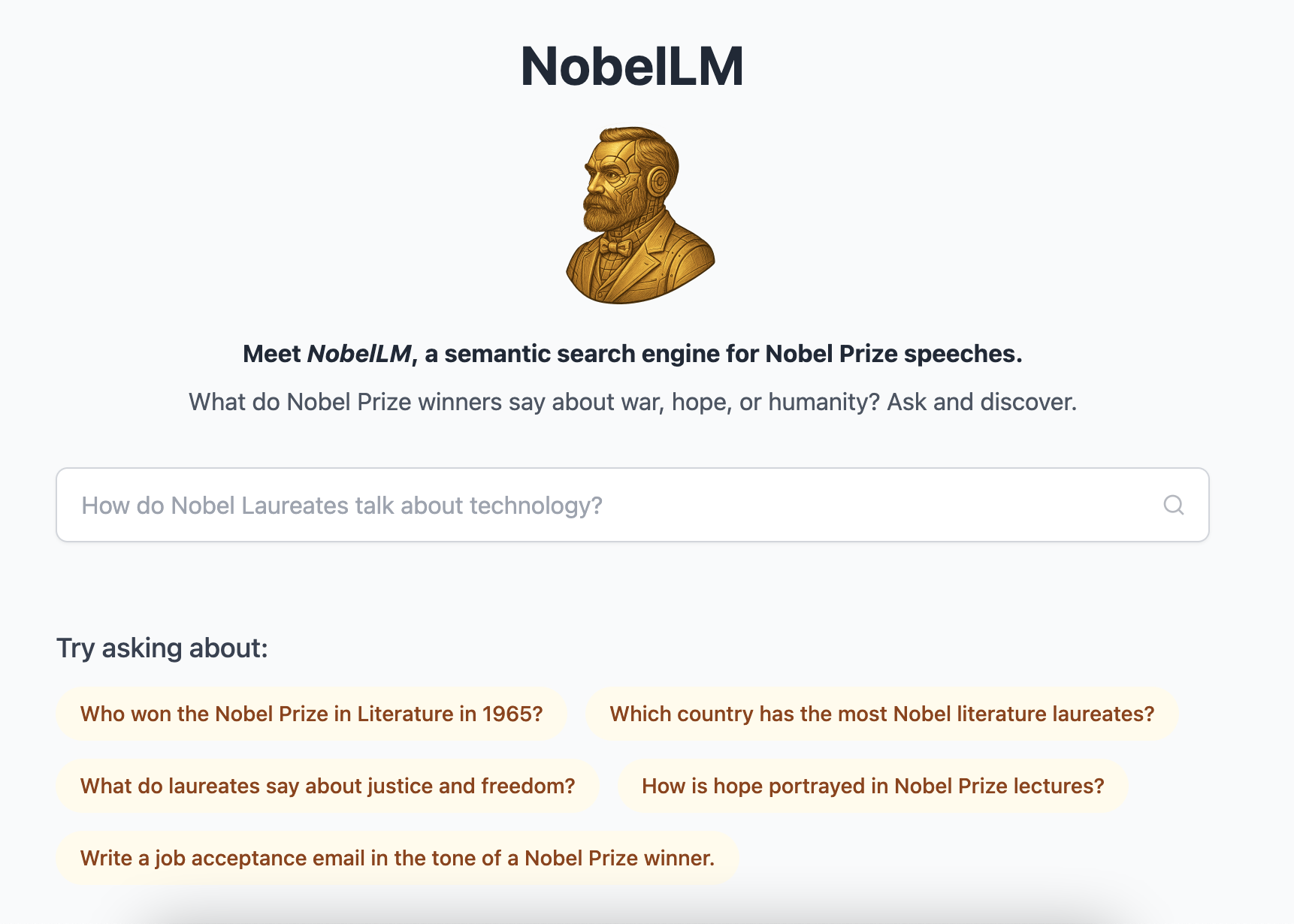

The NobelLM interface, showing suggested questions that demonstrate the four types of queries

The NobelLM interface, showing suggested questions that demonstrate the four types of queries

1. Clean Factual Lookups

Sometimes you just want a straight answer.

Query: “Who won the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1982?”

Response: Gabriel García Márquez received the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1982.

Nothing flashy—just a clean, grounded answer. For questions about names, years, or counts, NobelLM skips the heavy semantic search and uses a lightweight metadata lookup system. Ask how many female laureates there are, or which countries have the most winners, and you get the kind of reliable response you’d expect from any decent search engine.

2. Scoped Pattern Recognition

Sometimes you want to explore what specific authors or groups of laureates have said about a topic.

Query: “What does Toni Morrison say about freedom?”

The system searches specifically within Morrison’s speeches and returns: “Morrison emphasizes the importance of freedom as a precious human possession, highlighting its significance in the struggle for self-determination and against oppression. She expresses admiration for China’s unity in fighting for freedom and acknowledges the common love of freedom shared by different cultures.”

It’s not mixing her voice with others—it’s focused on her particular perspective and what she actually said.

Behind the scenes: NobelLM’s classification system can detect when your question is scoped to a particular laureate, gender, country, or time period, then narrows its search accordingly. Ask about “Swedish authors on nature” or “female laureates on identity” and it knows to filter the corpus before searching.

3. Broad Thematic Exploration

Other times, you’re looking for connections across decades of thought.

Query: “What do Nobel laureates say about the importance of literature in society?”

Here, the system pulls excerpts from multiple speeches and surfaces shared threads:

- Literature as a moral force and source of hope

- Writing as resistance and bearing witness

- Storytelling as identity, empathy, and cultural memory

This isn’t summarizing a single author—it’s tracing intellectual patterns across generations. Behind the scenes: The system identifies key concepts like literature and society, then intelligently expands to related ideas—culture, language, public responsibility, moral duty. It searches across the entire corpus and assembles responses from multiple laureates into something coherent.

4. Creative Generation

Then there are the weird, playful ones.

Query: “Write a job acceptance email in the tone of a Nobel laureate.”

The result opened with “Dear Esteemed Colleagues, I am deeply honored and humbled…” and ended with “…a renewed commitment to the power of literature.”

Dramatic, a little absurd, totally on brand. It won’t get you hired, but it shows the system can pick up on voice and style, not just content.

Behind the scenes: For creative requests, I sample 15 random but representative laureate acceptance speeches and use them as models for tone and voice. The system learns the formal, elevated register these writers use when accepting their prizes.

When It Gets Quirky

NobelLM handles most questions well, but it can get interesting with unexpected queries.

Query: “What do Nobel laureates think about social media?”

Response: “Based on the provided speeches from various Nobel Literature laureates, social media is not explicitly mentioned. The speeches primarily focus on themes such as the significance of the Nobel Prize, the role of literature in society, and promoting peace through cultural achievements.”

That’s actually good behavior—it correctly recognizes when something isn’t in the corpus and says so.

But ask about pets or animals and it might venture beyond the Nobel speeches into general knowledge about Hemingway’s cats or J.M. Coetzee’s advocacy for animal rights, which isn’t what it should do.

The system works best when you’re genuinely curious about what these literary minds have said about the big questions of writing, life, and meaning.

The Bigger Point

Human language is nuanced. Sometimes we want facts, sometimes patterns, sometimes creative exploration. I built NobelLM with the intention to handle these gradations—to recognize what kind of answer you’re actually looking for and respond accordingly.

A factual lookup needs precision. A thematic exploration needs synthesis. A creative request needs voice and style.

Try a question of your own at nobellm.com and see what happens. I’m curious what you discover.

Next week: The technical architecture behind these different response modes, and why intent recognition is harder than it looks.